:: 2022 :: 40cm x 50cm :: Acrylics, Inks and Markers on Canvas ::

In June 2022, I was fortunate enough to catch the ‘World of Stonehenge’ exhibition at the British Museum, which featured some stunning artefacts from Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age Britain, Ireland and Mainland Europe. I expected to be impressed by some of the ‘high-status’ exhibits – such as the Nebra Sky Disc and the Woodhenge display – but what really caught my eye were a small collection of early Iron Age wooden figures from Roos Carr, near Hull, East Yorkshire.

hello we are your friendly we are here to travel far to pass away… |

we ride a mystic with our detachable our removable our big blank |

liminal we are, who catch you we are not the stuff we are here to help you… |

Made from yew wood with dazzling quartzite eyes, and dating from around 800 – 500 BCE, these wooden figures depicting warriors on a serpent-headed boat have finely carved but somewhat uncanny faces and detachable penises, which may disclose fluid gender identities or simply the artists’ method, since the arms are also removable. They were found in the mid-nineteenth century by farm-workers digging up an irrigation channel, and are thought to have been deposited in a wooden box either in or under a waterway.

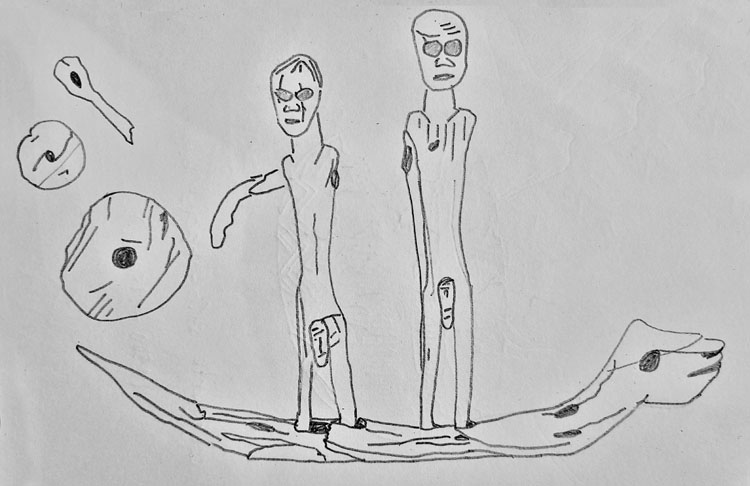

Quick Sketch of the Roos Carr figures, from life, British Museum, 30th June 2022

I found myself genuinely enchanted by these otherworldly figures on their strange serpent-headed boat, buried under a stream as if doubly liminal: under the world and under the water. I got a simultaneous whimsical as well as uncanny sense from them, and their staring quartzite eyes got me thinking about the magical or supernatural power they must have had for the people who gave them as a votive offering.

What struck me most about the power of their eyes was that they seemed to have been consciously depicted as glowing, shining or as bearing some kind of ‘potency’. This is something I have seen before in Bronze Age Aegean archaeology, as well as artefacts from neolithic south-east Europe. I also started to wonder what early Iron Age conceptions of the underworld might have been like.

Most of all, I was struck by the questions these figurines evoke. Who were they? Who peers out at us through those weirdly blank yet dazzlinly present eyes? Are we looking at otherworldly warriors, or underworld spirits? Are these some recently departed dead being sent off to some other world, or depictions of gods whose supernatural power is the mythical precedent for the courage and agency of earthly warriors?

I couldn’t help thinking of the early medieval Welsh poem ‘Preiddeu Annwn’ (The Spoils of the Underworld), attributed to Taliesin, which narrates a raid by three shipfuls of warriors on some misty otherworld to steal some great treasure in the form of spiritual wisdom or bardic knowledge. I asked myself whether we might be looking at warriors engaging in some heroic mythical event similar to that related in the poem. I wondered how long an oral tradition can survive - a thousand years or so between the early Iron Age and early medieval periods doesn't seem so far fetched, does it...?

As an artist, it is sometimes interesting to speculatively delve into the perceptual worlds of ancient peoples. Archaeology is often an etic practice looking from the outside in: being a science, it must always acknowledge its epistemic limitations, and the boundaries of knowledge beyond which it is not possible to pass. It must recognise that most of what ancient peoples thought and believed has been irrevocably lost.

We can never truly know what the experiential world was like for ancient people: we can only know that most of them would have lived their lives through emic perspectives. Ancient people didn’t bury offerings, for example, as expressions of their identity or to extend control over a landscape. Most of them gave expensive items as offerings to gods, or to ensure the blessed dead had a comfortable journey to the underworld, or some other, meaningfully human experience or belief.

Artists, however, have much more freedom, to contemplate, imagine, to hazard guesses… and indeed, throw all caution to the wind and take wild guesses, play with ideas and feelings, and walk among the clouds! To crash into all these questions with feeling and imagination, and clutch at what brief snatches of ancient inner life we might be able to glimpse, however fleeting or fictional. We can say: those gods, those dead spirits, they had names: they listened to prayers, were sometimes able to act supernaturally in the world, and influence the lives of those who made the offerings. These are their names, this is who they might have been...

We can justify such unbounded imagination, I suppose, by recalling the words of Roman poet Terence: ‘homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto’ meaning: I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me. Of course, in the end, we must honestly acknowledge our limitations, that what we create need not be real, now or in ancient times, that what we say about ancient artefacts might be as much about ourselves as they ancient people who made them. History and prehistory are created and recreated for each generation anew.

Such wild speculation is what I’ve done with this artwork: I’ve suggested an early Iron Age underworld experience by populating much of the background with some of the more surreal imagery from the late Nordic Bronze Age rock art at Bohuslan, Sweden.

Since a significant portion of the Bohuslan imagery is concerned with figures, possibly warriors, on boats, along with associated ritual scenes, and since Bohuslan is only a few days sailing across the North Sea from the East Yorkshrie coast, it seemed appropriate to envision the Roos Carr figures in this context. Given the British Museum also made this association, it might not be that wild a speculation after all.

Meanwhile, the poem which is associated with the artwork takes a similarly creative approach, but focuses upon and evokes that simultaneous whimsy and otherworldiness I felt on seeing these strange figurines for the first time.

we are here to help you…!