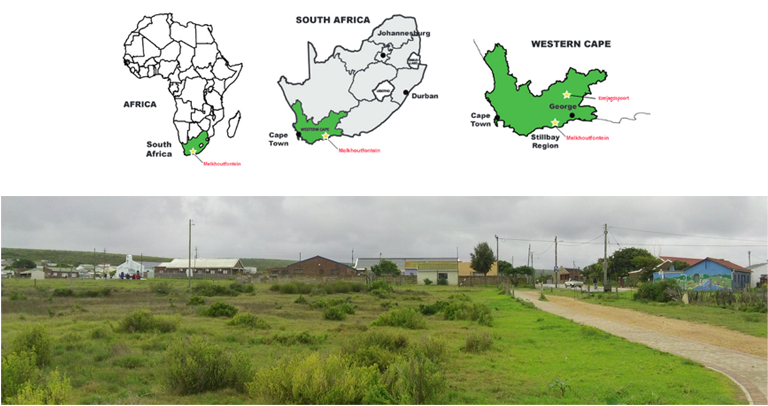

:: Melkhoutfontein, Stilbaai, Western Cape, South Africa::

:: February & March 2016 - March & April 2017 - February & March 2018 ::

In 2016, Bruce travelled to the township of Melkhoutfontein in the Western Cape of South Africa, to paint murals on the sides of houses as part of a multi-generational project of reviving cultural memories and recovering ancient roots. While there, a visit to a famous rock art site in the mountains enfolded Bruce into ancestral and visionary experiences of his own. This is a talk about how mural painting awakened an entire town, while a rock art image awakened Bruce into an emotive connection with land, water and shimmering shamanic images within.

I want to tell three stories at the same time. Fundamentally it’s a story of what happened when I went to South Africa to paint murals on a township in the Western Cape, and how my art awakened an entire town to their cultural memories, and helped to further the process of bringing dignity and pride back to the community. In the process, I was awakened too, enfolded by a famous image of Bushman rock art into an ancestral and visionary connection with land, water and shimmering shamanic images within. You’ll also see a few words in a Bushman language of South Africa. This language contains clicks / ! ǂ // and so you might see some unusual symbols every now and then! The name of this language, and the people who spoke it, is /Xam, which also contains a click sound.

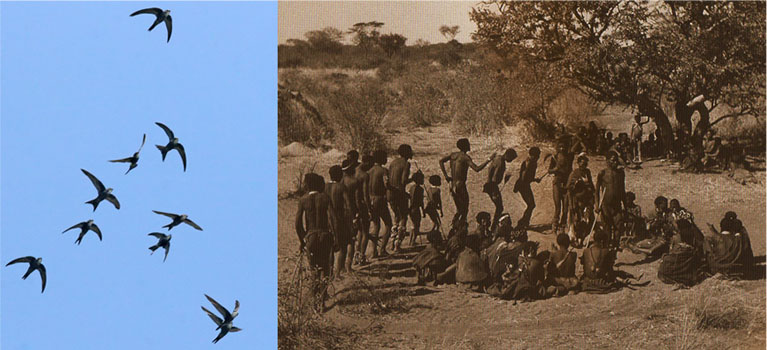

:: I AM RAIN - ENCOUNTERS WITH THE SWIFT PEOPLE ::

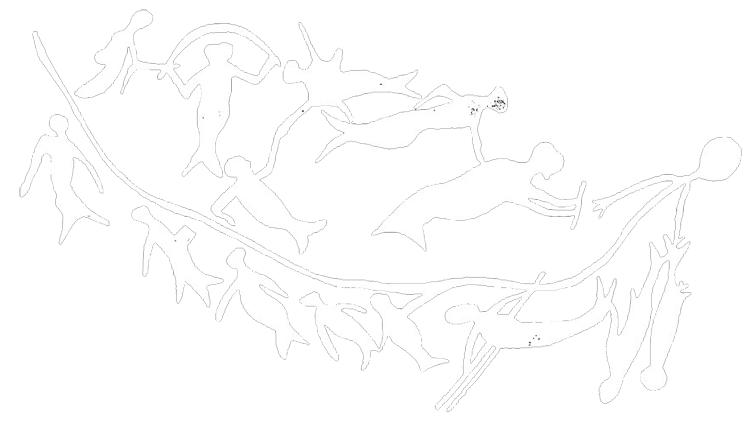

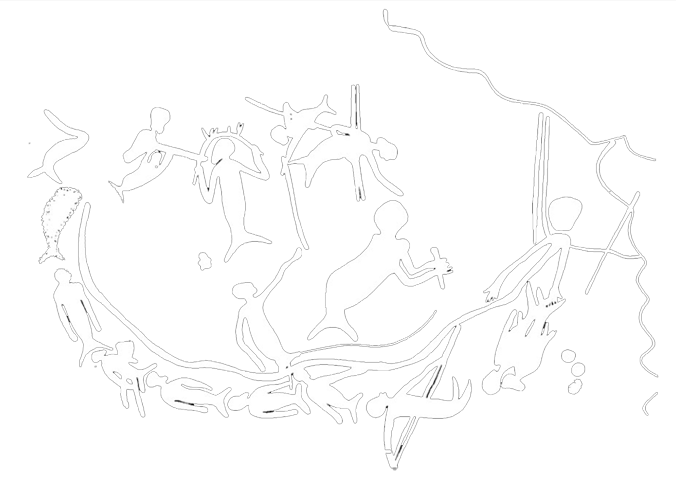

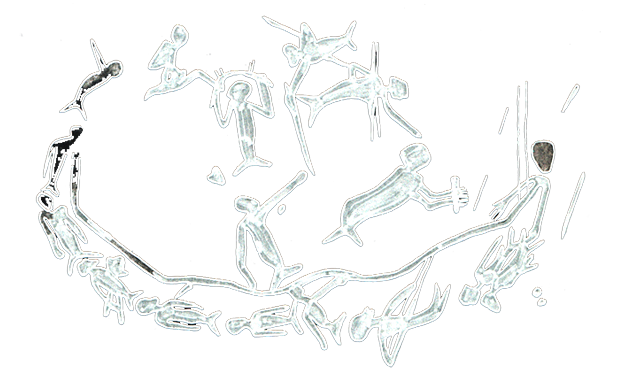

In the 1870s in South Africa, a few antiquarians became interested in Bushman rock art. One of them, George Stow, visited the site of Ezeljagdspoort in the upland dry landscape of the Karoo in the Western Cape, and made this drawing of a rock art image which quickly became famous. Everyone assumed that it depicts watermeide – mermaids who live in the waters and streams which cross the Karoo. Maybe the idea of mermaids reminds them of their European home somehow.

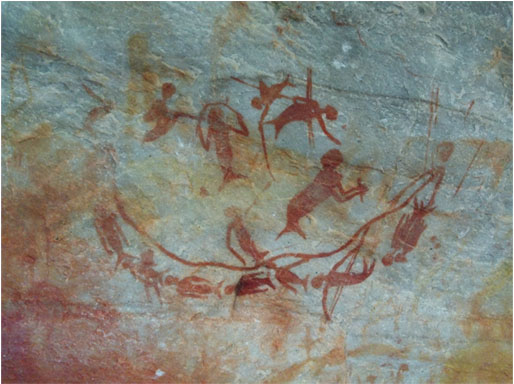

A few years later in Cape Town, researchers Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd asked the few surviving /Xam Bushmen from the Northern Cape what they think of this rock art image. One of them, /Hanǂkasso, had this to say: “I think that it is the rain’s navel that goes along here. I think that these people are addressing the rain so that the rain’s navel will not kill them… I think that these are the rain’s people – !khwa ka !k’e… they are sorcerors. They are rain’s sorcerors – !khwa ka !gi:ten… These people… the rain’s navel divides them from the other people. They are people, sorcerors, rain’s sorcerors. They make the rain fall, and the rain’s clouds come out because of them…”

No one really understood what /Hanǂkasso and his fellow Bushman people mean, so for many years their responses are ignored. White people like the idea of mermaids in the Karoo.

I was five years old when I had my first migraine. The moment I saw the first flickering shards of light and started simultaneously to go blind, I panicked. I thought I was going to die. My heart pounded and I spent the night in my mother’s arms crying and delirious. Throughout my childhood, migraines were a constant presence, and they were not just bad headaches. Flickering visuals would descend into terrifying visions and extreme photophobia, and I would run to my bed, retreating to the safety of darkness and silence.

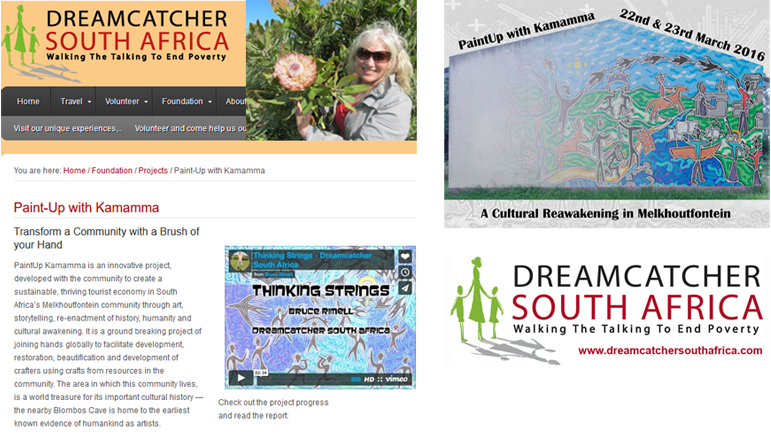

In early 2015, I was approached by Anthea Rossouw, the director of Dreamcatcher South Africa, asking if I would like to be part of a project called ‘PaintUp with Kamamma’ to create murals on houses in a township in the Western Cape of South Africa, with the aim of creating community pride and the retrieval of lost cultural memories. She had seen my artwork online and had an intuitive feeling that I would be right for the project and for the community. I said yes immediately.

In the 1970s, rock art researchers David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson returned to the images at Ezeljagdspoort, and explored the Bushman narratives collected a century previously. They argued that the indigenous accounts are not meaningless or random guesses about the images of fish-tailed people in the Karoo, but informed statements spoken through the medium of a culture that is now lost. Proceeding with considerable subtlety, they and their colleagues at the University of the Witwatersrand began to unfold the many layers of meanings.

Jeremy Hollmann suggested that many of the ‘mermaid’ images in the Karoo were in fact images of half-human, half-swift people – /kabbi ta !khwa – who represented shamans. He argued that the ‘circusing’ behaviour of swifts during mating season resembled the circular trance dances of Bushman shamans, and that when they flew into their nests (located in crevices in the rock face) at high speed, their sudden disappearance would have been interpreted as entering the spirit world behind the rock face.

He presented several images showing swift people emerging from crevices in the rock face to illustrate his point. Swifts are also rapid and skilful flyers, wheeling and darting, changing direction multiple times to chase down their insect prey, turning fast and with perfect control in the air – an excellent metaphor for the shaman!

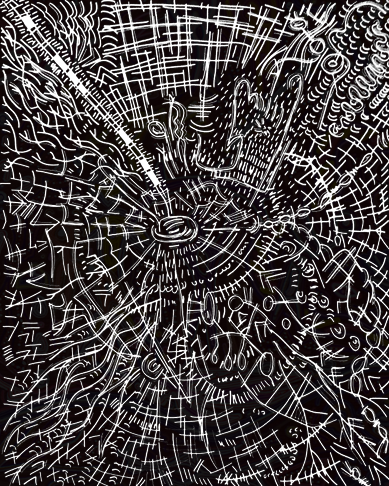

Migraines always begin for me with the ‘aura’, the sudden appearance of flickering lights and the steady loss of my vision. These flickering lights are hard to describe, but as well as being dazzlingly bright, they are also physically painful. Slowly the lights expand to my whole field of view, arrange themselves into a circle and then surreal, half-formed images fall out of this blind portal with immense force. My whole body turns electric, and even a simple touch from another person can send shock waves through me. I used to call it being on Lightning Mountain. Slowly over the years I came to, if not enjoy, then at least be able to experience without suffering, these visions of neuroelectric sensations and the physical force of light and sound.

Dreamcatcher South Africa is an initiative to help bring community pride and self-sufficiency to people in townships all across South Africa. In the post-apartheid country, many rural communities and townships have been ‘left behind’ as the cities reap the benefits of economic prosperity. Dreamcatcher works with communities to set up projects and small businesses, including the very successful homestay programme, where tourists can see the real South Africa far from the tourist trail, by staying locally in the townships.

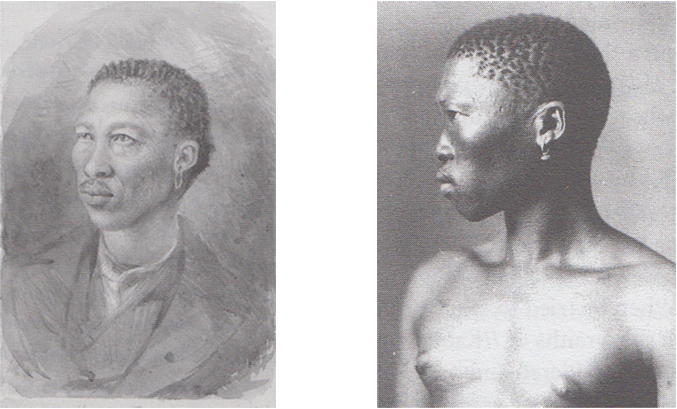

The heart and centre of the Dreamcatcher Foundation is Melkhoutfontein, in the Western Cape, the place where it all began. Twenty-five years ago, this community was in desperate poverty, with the highest rate of tuberculosis in South Africa, and some of the lowest educational attainment. The people are mostly mixed-race, descendants of white settlers, Khoekhoen herders and Bushman hunter-gatherers, whose cultures were destroyed some 200 years ago during the colonial era.

Their descendants were first enslaved, and then removed from their lands to a township during the apartheid period, and many of their ancestral cultural memories were lost. When Anthea came to live in the community, she was charged by one of the community elders, Moses Kleinhans, of becoming the town’s Dreamcatcher, to bring life back to the people after so many years of pain.

David Lewis-Williams suggested that the /Xam Bushman people of the Karoo understood swifts and swallows to bring the rains which watered the land. This in turn caused the wild onion leaves to flourish, feeding both the people and the animals on which the people preyed. He quoted Dia!kwain: “Our mothers tell us that we should not throw stones at the swallow because it is the rain’s thing – !khwa ka //ki… We can see that it is not like other little birds that eat earth… When the rainclouds are in the sky, then the swallow flies about… Our mothers used to tell us that the swallow is with the things which the sorcerors take out and which they send about…”

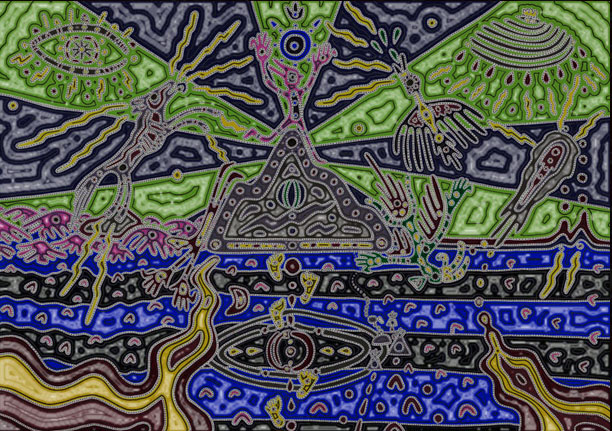

In my early twenties someone gave me a book of Bushman rock art. As I turned the pages I began to feel strange, almost sick. The images of animals and humans were one thing, but the lines of light and abstract geometric images… well, I had seen these before. I had been seeing them since I was a child. As I turned page after page, I identified with so many of them, remembering how some of them could be physically painful, while others almost had the sense of a song about them.

Or perhaps, this line of light, along which I had moved during a particular migraine vision in my teens. Images of the blind portal out from which strange visions appeared. I was instantly and forever attached to these images, across thousands of years and thousands of miles. I don’t think my friends really understood, but until that day when I opened that book, I had never truly known what these visions were…

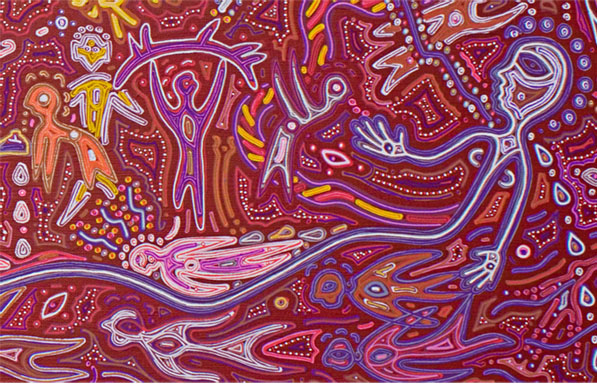

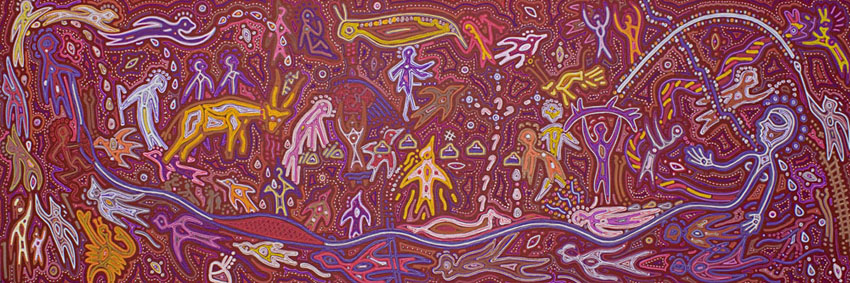

As Anthea and I discussed the ‘PaintUp’ mural project, I began to design some of the murals, turning to the local Bushman rock art and the prehistory of Melkhoutfontein’s people. Despite what they had been told by colonial and apartheid authorities, they were not nobodies – they have deep roots and a rich history in the landscape where they live. Bushman rock art in the mountains not far from the town, including the famous Ezeljagdspoort image, became enfolded into the designs.

As a metaphor for community transformation, the Swift People are a beautiful image. Just as the Bushman peoples once danced and transformed themselves into swifts to effect potency and healing, so the community of Melkhoutfontein was flying up into another world, a new world where they could be truly proud of themselves as people and become reminded of their deep and profound history and its legacy. As I began to paint the first mural, neighbours came out to watch, and then understanding that something was beginning, over the next few days some of them began to tidy up their gardens. Some even began painting their own houses!

In March 2016 I had the good fortune to visit the Karoo, during my first visit to Melkhoutfontein and the first round of painting murals there. My guide, a true Karoo naturalist called Katot, took me to a nature reserve called Pieter’s River where we beheld a beautiful frieze of polychrome rock art. Arrays of elands, elephants, lines of light and dancing shamans emerging from crevices in the rock face greeted us in all their visual and supernatural potency. I was shimmering. On the drive back, Katot casually suggested we take a little detour into a little gorge called… Ezeljagdspoort! I almost went crazy with excitement. Yes I said. Let’s go there, yes.

We had to wade through a river heavy with reeds, then fight our way through bush and fynbos to reach the little rock shelter where the famous image is located. And suddenly there it was halfway up the wall of the shelter…

The swift people dancing a circular trance dance as a storm bears down on the valley. Two things are happening. The first is that they are dancing around patients who are sick and need to be healed. The second is that they are becoming swifts to control the rain: they dance around the rain’s navel – a violent storm cloud – both to ward off a dangerous flood from where they are living, and to make contact with the supernatural potency embodied in the lightning – this long trail – so that they may become stronger shamans. They are shamans of the rain - !khwa ka !gi:ten – and each of them makes contact with the rain’s navel, the storm, to acquire potency…

I shimmered, I truly shivered with electricity there in the shelter as this little rock art image stormed into me. And then I noticed above my head: a swift’s nest. As I stood watching, a dark shape flashed around the shelter, made a loud chirp and disappeared: the swift whose nest it was had entered the shelter, but seeing us present, flew rapidly away for safety. We left soon after, but I could not let go of my excitement and my inner shimmering…

For days and nights afterwards, the swifts were with me. I returned to Melkhoutfontein, greeted by torrential rain (just 10 minutes inland there had been bright sunshine) and as I returned to my room in the township, there were swifts on the power lines next to my window. That night, the weather turned humid and in the middle of the night I awoke in burning heat, sweat dripping from me, my whole body tense and electric. I couldn’t feel my hands or my legs, and in half-dream, I understood I had turned into a swift. Every time I closed my eyes, I felt rapid movement. This half-human had become half-swift, and the sweat was my rain. I dreamed and flew about, over the township, and over landscape towards the Karoo. Some part of my soul seemed to be left there in the shelter. This happened several nights in a row.

I began to make connections that I hadn’t realised before. Shamans everywhere speak of lines of light, tracks of potency along which they travel to do their work. The /Xam Bushman called them ‘thinking strings’ – !nuin //kau//kaugen – that connected animals and people, children to their ancestors, the land to the sky. I saw them in the rock art, and I was dreaming of moving along them in the South African landscape. Suddenly I realised: I had been seeing these in my migraine experiences, and other visions for so many years. I found myself deep in the South African landscape and suddenly knew why, since I was a child, in every landscape I had ever lived, I always sought something magical or ancestral. I was always seeking these thinking strings, ringing in the earth and the sky, listening to their songlines without ever quite knowing what they were.

Just as I had been awakened by the rock art, so too were the people of Melkhoutfontein beginning to wake up to the impact of the work I was doing. There was magic in these images for sure, but there was also dignity, respect and remembrance. Imagine: not just a single individual standing in a gallery and enthusing about your painting, but an entire town of 5000 waking up to their own history through the images you are creating. Children stand and watch you, teenagers get excited and ask you what it all means, elderly women stand quietly until your eyes meet theirs and then they smile, or nod in satisfaction, or in one case, burst into tears.

So this is the magic I made, and I want to share some of the murals with you, so that you can know the magic of Melkhoutfontein, and the true brilliance of the people and their history, from the beginnings of human culture at Blombos, through the Bushman peoples, the Khoekhoen and the Strandlopers, and the modern community.

The first 'Swift People' mural painted in Melkhoutfontein (Warren & Surita's House)

Painting Swift People rising up a chimney (Marthinus and Regina's House)

Scenes of Bushman and Khoekhoen hunting life (Samantha's House)

The timewalk of the ancient and modern history of Melkhoutfontein's people (Frank's House)

Red Ochre Dancers at Blombos (Willem's House, with Jason painting)

From Here To Everywhere (Miena's House)

Samantha's House and Miena's House together

Susan is very proud of her mural of the landscape at Blombos cave

After I came home, I found myself sitting with a friend, and I happened to show him the image of the Ezeljagdspoort rock art which was on my phone. I found myself simply saying to him: "I keep this with me because I am Rain. I took me a long time to realise, but it’s true. I am Rain." He looked at me for a moment, then said: "I have no idea what that means… but it’s so beautiful..."

So this is what I say of myself now: in the /Xam language, n /ne kan e: !khwa ~ I am Rain… I don’t always know what it means, but as an experience, it is always something beautiful shimmering within me, one of the many things that connects me forever to the land and the people of the community of Melkhoutfontein...

Bruce Rimell, Summer 2017

:: POSTSCRIPT 2018 ::

I have been visiting the community of Melkhoutfontein, and creating more murals there, each year now since that first visit in 2016. Around half the murals in the town were painted or designed by me, and it truly makes me feel so proud and honoured that this open-air gallery of art so strongly features my work, and that the people have taken to it so warmly and deeply. The Swift People are a prominent feature among the imagery…

One of the truest purposes, it seems to me, of an artist is to lay out the structures and foundations of a new world, and make it explicable to the people. Three years ago, when I first started thinking about mural designs for Melkhoutfontein, I dreamed up the Swift People - images from the local Bushman rock art of people transforming into swifts - as a symbol of transformation for the community. And in the past three years, the people of Melkhoutfontein have picked this up and run with it: they've truly understood, and there are Swift People painted all over the town now. If I can truly call myself an artist who aims to create and structure new worlds of wellness and wholeness for people, then it is really here in Melkhoutfontein that I have earned that name. I continue to be so honoured that my Swift People symbol has been taken so much into the hearts of the great people of Melkhoutfontein…

...is it strange to say I have noticed that whenever I start to paint swifts in Melkhoutfontein, the wind blows up and sometimes there are spots of rain? ...is it strange to see them flying about in these sudden breezes while I am painting? ...is it odd that on both mornings in March 2018 when I painted these two murals, there were unbidden showers of unseasonal rain...?

Bruce Rimell, March 2018